ANTÔNIO CARLOS ELIAS

Contratempo ou Locus suspectus.

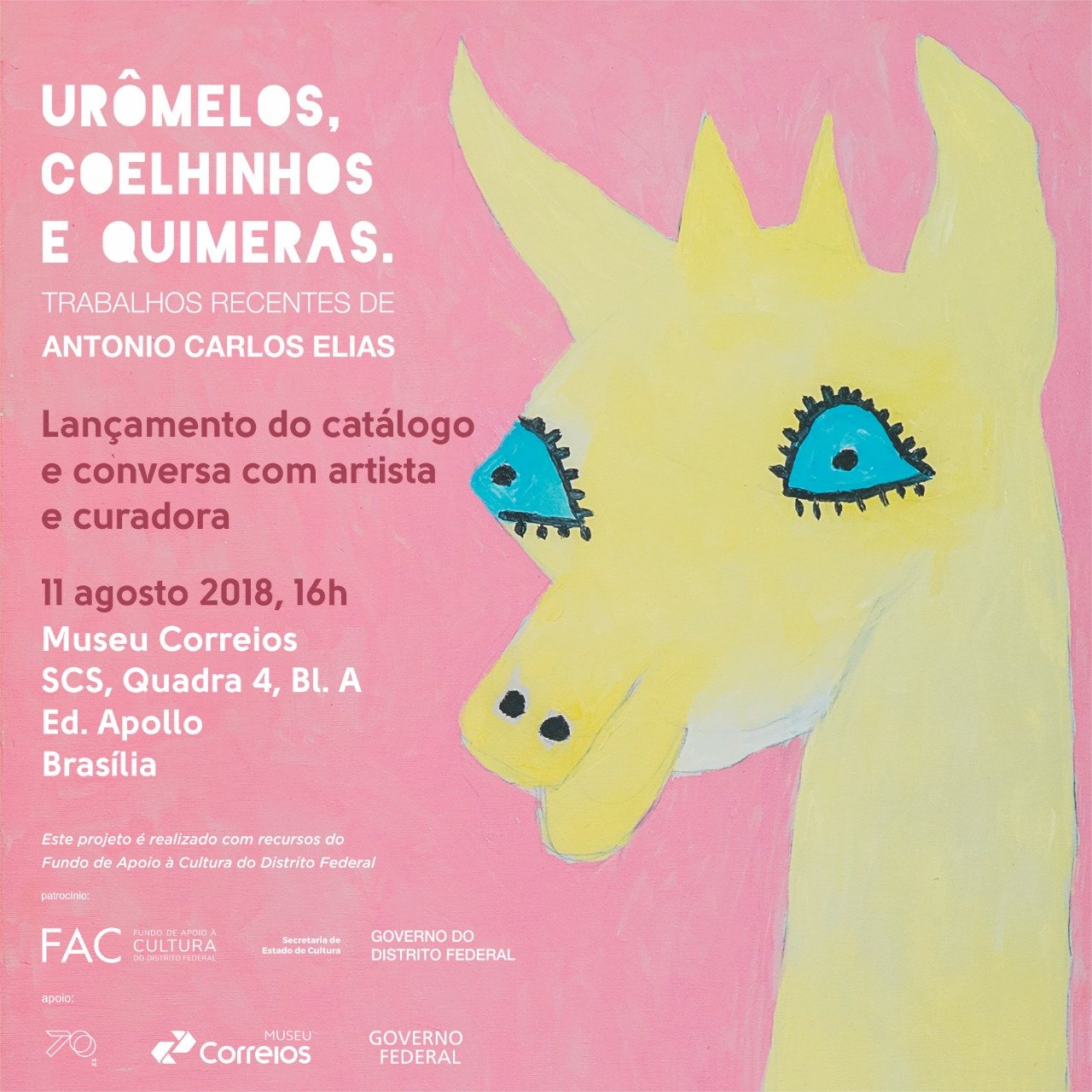

On the exhibition Urômelos, Coelhinhos e Quimeras: Trabalhos Recentes de Antônio Carlos Elias.

(Text for the exhibition wall)

Once we cast our gaze upon what Antônio Carlos Elias creates, something shifts within the realm of certainty.

There is no going back after encountering his work. It’s as though something escapes the habitual frame and enters an anachronistic space, propelling us toward a parallel universe, an alternate reality.

Perhaps these works evoke a sensation akin to that experienced by the child we once were—described by Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero in their Manual of Fantastic Zoology—when, on their first visit to a zoo, they see animals never encountered before.

Rather than recoiling in terror at the strangeness of such a peculiar garden, the child delights in it, prompting the authors of this narrative about the interplay between reality and the fantastic to pose a singular and mysterious question: How can this phenomenon, both common and enigmatic, be explained?

This exhibition showcases a body of work created since 2015, marking a new chapter in Elias’s trajectory.

What could have been presented as a retrospective, given the artist’s longstanding career, instead signals the beginning of a new story, breaking away from the constraints of a preexisting creative cycle.

It feels fitting to consider this new phase through the lens of the concept of entropy, as outlined in the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

This concept is often employed to address transformations in contemporary art, which frequently challenges the balance of systems.

For Elias, entropy serves as a metaphor for reassessing his artistic past: recognizing when something in his poetics no longer holds the same meaning and envisioning a new direction for his work.

The entropic nature, which suggests that things tend toward an end, is counterbalanced by self-regulating mechanisms that infuse fresh air and meaning into the poetic.

Approaching these installations reveals them as both phenomenon and noumenon—there is an unintelligible layer beyond what meets the eye.

I dare say they awaken a kind of sensibility that Sigmund Freud categorized as the uncanny, where something feels simultaneously familiar and unsettling: a singular landscape presenting itself to our eyes and striking at the core of our senses.

Attempting to precisely define the origin of the strangeness elicited by these installations seems futile and unnecessary, for it is the uncertainty of what we perceive that sustains the vibrant energy of these works.

They appear to form a fantastic microcosm, resembling tableaux vivants but devoid of human figures enacting situations or anchored to any temporality.

In this microcosm, untethered from any clear narrative, the colorful, vibrant paintings populated with diverse images seem to propel outward the white plaster sculptures made from Paris plaster (a material frequently employed by Elias).

Once materialized in the sensory realm, these sculptures serve as a reminder that reality is closer to the supernatural than we might imagine.

Would it be fair to describe what we see as bestiaries, as narrated by Julio Cortázar in his eponymous work? ("Before falling asleep, he had a moment of horror imagining he might be dreaming.")

Or are they reflections of a scientist who traverses the world of soulful fiction?

Or perhaps both?