Fábio baroli

(text for catalog)

Matutar-se.

The set of paintings selected to compose the exhibition Deitei para repousar e ele mexeu comigo emphasizes aspects related to what the artist calls “Antropomatutologia,” meaning the knowledge of the rural subject in context. The curatorship chose to bring together the pictorial production of Fábio Baroli, initiated in 2007, seeking to intertwine the painter's research on regional imagery with the curator's research on Brazilian art history. The exhibition displays paintings from series made between 2013 and 2015, which center around his experience in Uberaba, Minas Gerais, his hometown. The chosen series are Muito pelo ao contrário (2013/2014), Meu matuto predileto (2014), O vendedor de galinhas (2014), A terra do Zebu e a casa do caralho (2014), and Quando a seca entra (2015), in addition to the painting that lends the title to the exhibition: Deitei para repousar e ele mexeu comigo (2015).

This selection of works aimed to highlight the rural dimension of life, from which we, the readers of this text who visit galleries and museums, and who live in metropolises, are generally detached. We are also separated from other layers of life by the compartmentalization of time to which we are subjected [or to which we submit ourselves]. Or still, we are distanced by the excess that consumes our days, much like fire consumes wood. There was a curatorial desire, supported by the exhibition design, to intensify the contemplative gaze upon the painting, adjusting to the slower rural time and the everyday habits of living and speaking, where hours pass leisurely, and events do not align as immediately as they do with the facts that govern life in large capitals.

The colloquial and popular language and the relationships established between individuals during moments of socialization inform and constitute the visual fable of the artist about his experience from the interior of Brazil, aligning with a question posed by the Cuiabá poet Manoel de Barros in Menino do Mato: “Is vision a resource of imagination to give words new freedoms?” Although this wasn’t the poet’s intention, there it was, in the form of a question, a phrase pointing to ways of reflecting on the visual prose, full of puns, that Fábio Baroli presents us in this exhibition.

It is impossible, as we reflect on what Baroli does by painting in a figurative and realistic way, not to think about the relevance of painting today, in a landscape of technological urgencies that blur the gaze and thought in the rush of seeing, processing, and considering. A movement too dynamic for painting, which demands a slow gaze; something like what Alberto Tassinari says while reflecting on Merleau-Ponty's phenomenological texts about painting: “For one to look from one side to another in a single perception, it is necessary that the present, before being an instant, be a kind of region with vague contours where the future flows into the past from all sides.”[1]

Leaving a gap for the gaze (mind, spirit) is part of one of Baroli’s procedures in constructing his pictorial space. Generously, the artist understands that painting can be an open field for interpretations: it is constituted by the relationships between shapes, planes, and stains, and even though (the idea of) reality is depicted, something in it escapes, as the work is a space for thought mobility. The artist solves this insoluble by leaving spaces unfilled, by associating images from different sources within the same plane, by scrambling its orthogonality and “cutting” the canvas through geometries, and by leaving visible stains and splashes.

Even photography serves to aid in this dissolution of forms and planes, constructed to point out the instability of the real, urging us to see it as it is, in two ways: photography enters the scene as a base device allowing the painter to record situations that will serve as references for new paintings, while also presenting itself as a language. Together, painting and photography form an alliance to emphasize and scramble the real.

And if the painter, by activating the pictorial plane, also transforms it into a kinetic field, providing conditions for the gaze to walk across its surface. These paintings provoke durations in time, expanding perceptual horizons.

In this exhibition, there are stories being told in snapshots, which slowly unfold. Let us approach them.

Landscape as a Shield.

It is curious to think about the temporal transitions that connect subjects to spaces, distorting history. Here are Baroli’s paintings, in a territory that was once a route for pioneers coming from Uberaba towards Goiás in the 18th century. Now, in the process of migration, it is the artist who exchanges with the place artistic and cultural goods he brought with him. According to Peruvian writer Cornejo Polar, he becomes a “subject who simultaneously receives the gift and the condemnation of speaking from more than one place,” affirming himself “as a subject who resides, in part, in not forgetting any stop along his itinerary, in not accepting being deprived of freedom from various places.”[2]

The return to Uberaba in 2012, after ten years away, was crucial to establish new foundations for his painting. Baroli resumes his stay in his hometown while still maintaining ties with Rio de Janeiro, so metropolitan. From this passage/return situation arise the paintings Intifada and Vendeta.[3] As the artist says: “The place, indeed, influences the way of thinking, and this influence is reflected in the work.” With each phase of passage and contamination by the place of residence, themes accumulate, mixed, glued, and assembled, setting the tone for his artistic production. “Pra lá de dois pé de Gabiroba,” a 2015 site-specific polyptych created for this exhibition, serves as an index revealing the status of landscape for the painter, just as Venice was for Canaletto, L’Estaque for Cézanne, or Rio de Janeiro for Luiz Zerbini.

Painting the landscape is to articulate the relationship between the time of those who live the place and perceive it, understanding that it will never be possible to encompass it entirely, as what we see is just a part, a glimpse of the real, always imagined. It is a fold in the artist’s memory. “Pra lá de dois pé de Gabiroba” connects us with many other landscapes we have seen and with which we identify, but it also presents the paths Baroli found, resulting from his idiosyncrasies related to the theme, singularizing it. In this vast landscape of many parts, the artist stitches together perspective planes and viewpoints, leaving incomplete spaces (partially “filled” with painting directly on the gallery wall, giving the idea of continuity and presence to what is there).

As Mario Pedrosa wrote in 1958, when commenting on Brazilian painting, the enduring feeling: “It is from the encounter with the same problems and the personal solutions found for them that true continuity is established in the evolution of our pictorial time.”[4] The large landscape, specifically conceived for the exhibition, is situated at the gallery’s entrance, inviting the viewer to enter the rural scene set by the curatorial selection, based on Baroli’s concept: Antropomatutologia.

Defining this journey in time as antropomatutologia was, according to Baroli, an attempt to update the theme, positioning the rural subject as a protagonist in a contemporary narrative. He began the process by executing paintings inspired by anecdotes and puns typical of the Minas Gerais region, and continued transitioning in a pictorial elaboration that, still based on rural language, was continuously linked to the themes of his interest since 2007: eroticism, transgression, childhood imagery from the interior, regionalism, portrait, landscape, photography, collage, and appropriation.

The Rural Subject in Exhibition Context.

The Outside.

The condition of being another is a learning experience. Baroli, as he moves from one place to another in his professional journey, combines experiences and perceptions in this movement of displacement—and here we are not just talking about personal experience, but about the matter that connects subjects on a national and global scale—to turn them into elements of painting. Bringing the “matuto” to the art gallery is to take it out of the isolation to which it has historically and socially been relegated and (re)place it within a non-documentary field of vision, as it usually is, and into the artistic field, because, after all, we are talking about painting.

Historical twists transcend times and spaces, connecting moments in the history of art and taking us, as in a leap, to meet a certain Brazilian painting of the 19th-century regionalist style. Baroli’s paintings, figurative and supported by photography as a supporting device, attest to his fixation on the realm of the plausible. Some say, when looking at his work, particularly at the paintings referencing the regional, that we are faced with an anachronistic painting, both because of the figurative degree of reality we encounter (as if his painting were outside the register of time and space, belonging to a past moment in art history) and because of the subject matter he focuses on. If we accept this hypothesis, we might dare to say that it is precisely this space-time collision, which takes the work out of the expected register, that we find in contemporary art, or in one of its facets.

Almeida Júnior[5] is the Brazilian painter, in his naturalistic and regionalist phase, who most quickly comes to mind when we seek to address the relationships that connect one point to another in these paintings. Others could be the painters of the same era, suitable for the dialogue with Baroli, but Almeida Júnior, with the less romantic and patriotic way in which he handled regionalist themes, best fits this endeavor.

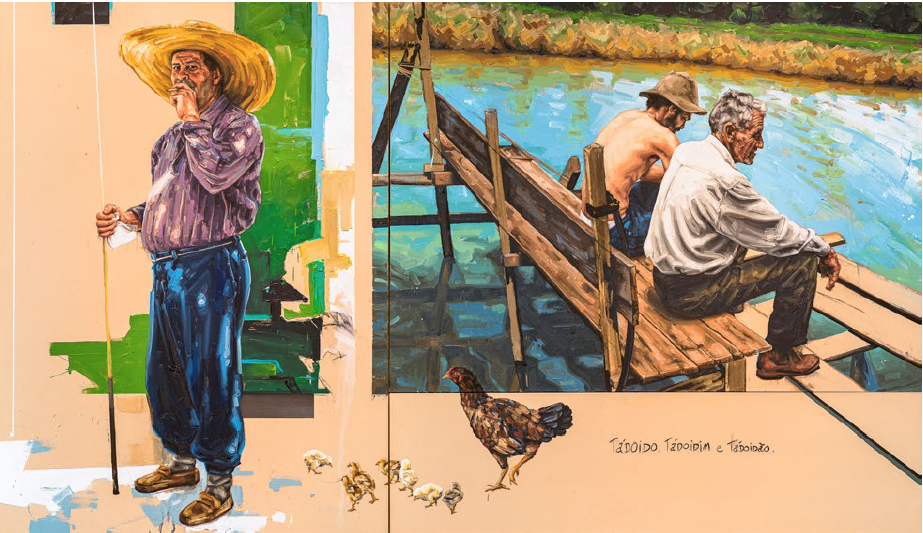

Thinking about the possibilities that lead to reflection and that link this moment of Baroli’s work to the historiography of Brazilian art, both past and present, was fundamental in formulating the curatorial concept. The painting Caipira picando fumo by Almeida Júnior became the ideal image to start the conversation. Meu matuto predileto, from 2013, a painting from the eponymous series, became the focal point and radiating axis of the curatorship and exhibition design, arranging new associations between the paintings, also linked to their technical and formal qualities.

The “being outside,” which constitutes much of life in the countryside, persists beyond the natural landscape that foreshadows the exhibition. Entering the exhibition space does not mean closure, but rather maintaining a presence in the external space of the small town, only in new contexts. In Cê gosta de laranja, from 2013, and Não mexo mais engato, from 2014, fragments of day and night present collective ways of being and existing. They coexist with the painting Vazou na braquiara, from 2014, which acts in the space as the “reverse” of the bucolic and contemplative landscape that welcomes us at the entrance, signaling the path that leads us to Uberaba, where roosters and hens (Lourdinha, Chris, Lassim e Madá, from 2013)[6] still scratch and accompany us during the stroll through the “environment” of the gallery.

The Inside

However, the transit through the city and rural life does not end in the socialization and communication of groups outdoors. The luminous side of life is shared by the dark side of existence, both in the city and in the countryside, regardless of creed, origin, ethnicity, etc. These are oppositions, just like wordplay, which includes puns and linguistic mannerisms. As Baroli quotes, paraphrasing his father, Basílio, represented in the polyptych that lends its name to the exhibition: “The problem with painting is the tinterrada.” And, as everything has two sides, Baroli adds: “If we pronounce it quickly, we hear ‘tinterrada’; from the pun’s perspective, it’s an ‘enterrada em ti’” [7].

The present, as dynamic as we witnessed in the previous section, meets the past at another moment in the curatorship/exhibition design. Here, paintings make up a more subjective constellation, belonging to the artist’s intimate universe, but with which we also identify. In these paintings, a mood of melancholy and remembrance prevails. It is important to emphasize the role played by photography, which, while maintaining its function as a recording device for the paintings, more strongly adheres to the images that gave rise to these specific works.

Both in Quando a seca entra from 2015, and in Deitei para repousar e ele mexeu comigo from 2014, we begin to inhabit the realm of the intimate. The photographs from family albums and the absent father are transformed into paintings that return—through their connection to an emotional field of memory that is so dear to the painter and to all—once again as photographs in the imagination of those who view them. This sensation is enhanced by the use of ochres, whites, and grays that Baroli applies to these images. These small paintings, arranged according to an arbitrary/sensitive logic, allow the viewer to develop a series of narrative associations. And, as if to live with losses, we needed an expression that could account for them, we come across Toca uma pra mim, from 2015, an object of solitary triumph, wrapped in a melody that we can only access by sharing with the figures the loneliness of the scene.

Painting continues to be a projection of a reality still to come, because we always know little about it. And the painter dreams, mixing times and spaces that navigate between what he fantasizes and what he lives. In the dark room, we are an audience in a cinema screening: a battle takes place in the courtyard of the Church of São Domingos in Uberaba, at night. Under the influence of warm colors—yellows and oranges—and dark tones: blacks, blues, and violets, which absorb everything, the scene from A terra do zebu e a casa do caralho, from 2014, unfolds, gradually transforming before us. The clash seems to occur amid diverse temporalities, reinforced by “patches” of associated and juxtaposed planes—scenes upon scenes—that give high energy to the quadrilateral that contains, with great difficulty, its characters and objects. The architectural structures—church and skyscrapers—at opposite ends mark the conflict zone, indicating that the peaceful coexistence of two worlds is only possible in the realm of utopia and that the clock continues to count the hours. The viewer is also a character: a witness to an always continuous present, which the painting reveals each time it is looked at. Is this a painting of foresight?

But, from the future, some things are certain: we know what chickens and roosters do not yet know, but what Grandma Dica, represented at a moment of total satisfaction with her recently made task, has already taken care of. Simple as that.

TASSINARI, Alberto. Quatro esboços de leitura. In: MERLEAU-PONTY, Maurice. O olho e o espírito. São Paulo: Cosac&Naify, 2004. p.158.

[2]. Cornejo Polar, Antonio. Una heterogeneidad no dialectica: sujeto y discurso migrantes en el Peru moderno. Revista Iberoamericana. Vol. LXII, n.176-177, Julio-Diciembre 1996, p.840.

[3] In the year he returns, Baroli begins the "Intifada" paintings, a triptych measuring 220x480 cm, depicting 24 children and adolescents, facing the viewer, blocking a street in Uberaba, armed with toy guns and ready for the uprising. And Vendeta, a set of smaller paintings, with close-ups of each of the children from the triptych, with their “weapons,” causing a closer connection and reinforcing the tension present in the conflict expressed by the painting.

[4] PEDROSA, Mário. Problemas da pintura brasileira. In: Acadêmicos e modernos. Textos escolhidos III. São Paulo, Ed. da Universidade de São Paulo, 2004. p. 300.

[5] José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior (1850-1899), Brazilian painter and draftsman, born in the state of São Paulo.

[6] These four paintings belong to the series O vendedor de galinhas, a 2014 painting.

[7] Excerpts taken from Fábio Baroli's text to introduce the series Muito pelo ao contrário.

Sem título.

Série O Vendedor de Galinhas e Meu Matuto Predileto. Óleo sobre tela.

150x110 cm,

2013.