André Amaro

The Expanded Three: Stories Told Under the Open Sky

(Book Text)

It was in the name of the number three that André Amaro shared with me the story behind a set of 15 photographs, intended as objects of analysis and writing. The number three was the guiding motif that shaped the creation of this group of images. It spurred him to observe scenes to be captured and narrate them. Yet, I must admit, it was the visual attributes of these photographs that drew me in—something that often happens with black-and-white photos due to the clarity and emphasis that scenes, objects, and people retain in the monochrome world.

At first glance, I had the impression I was looking at analog images when, in fact, they were captured digitally. Realizing this, the photographs took on a different perspective, offering another dimension of interpretation. Somehow, technological processes connect temporalities, associating past and present techniques, infusing these photos with contemporary qualities. My initial perception of these images as analog relates to the aura analog photography conveys, with its varying shades of gray and nostalgic tone, reminiscent of photographs from decades ago. This impression aligns with the deliberate craftsmanship in their composition, evoking the sense that care was taken to give the landscapes a handmade quality. Australian art historian Geoffrey Batchen, reflecting on the history of photographic production, noted that an enduring feature of photography is the "manufacture" of the image—a constructed artifice inherent to the photographic process.

The number three, in itself, unbound from any substantive or story, brings us to its basic notion as the sum of two plus one. According to philologist Antônio Houaiss, it also relates to the expression "three by two," signifying regularity and frequency. This idea of harmony and proportion, which Houaiss connects to the number three, likely originates from the extensive literature rooted in the symbolism of the Holy Trinity and its correspondence to the harmony of mind, body, and spirit: the perfect triangle. From this foundational notion, the number three branches out into endless linguistic and conceptual derivations: tresandar (reek), trescalante (pungent), três-corações (three-hearts), tresdobrado (tripled), tresnoitado (three nights), and so forth. The number three invites reflections on the three dimensions of space and the three states of time—concepts crucial when it comes to photography.

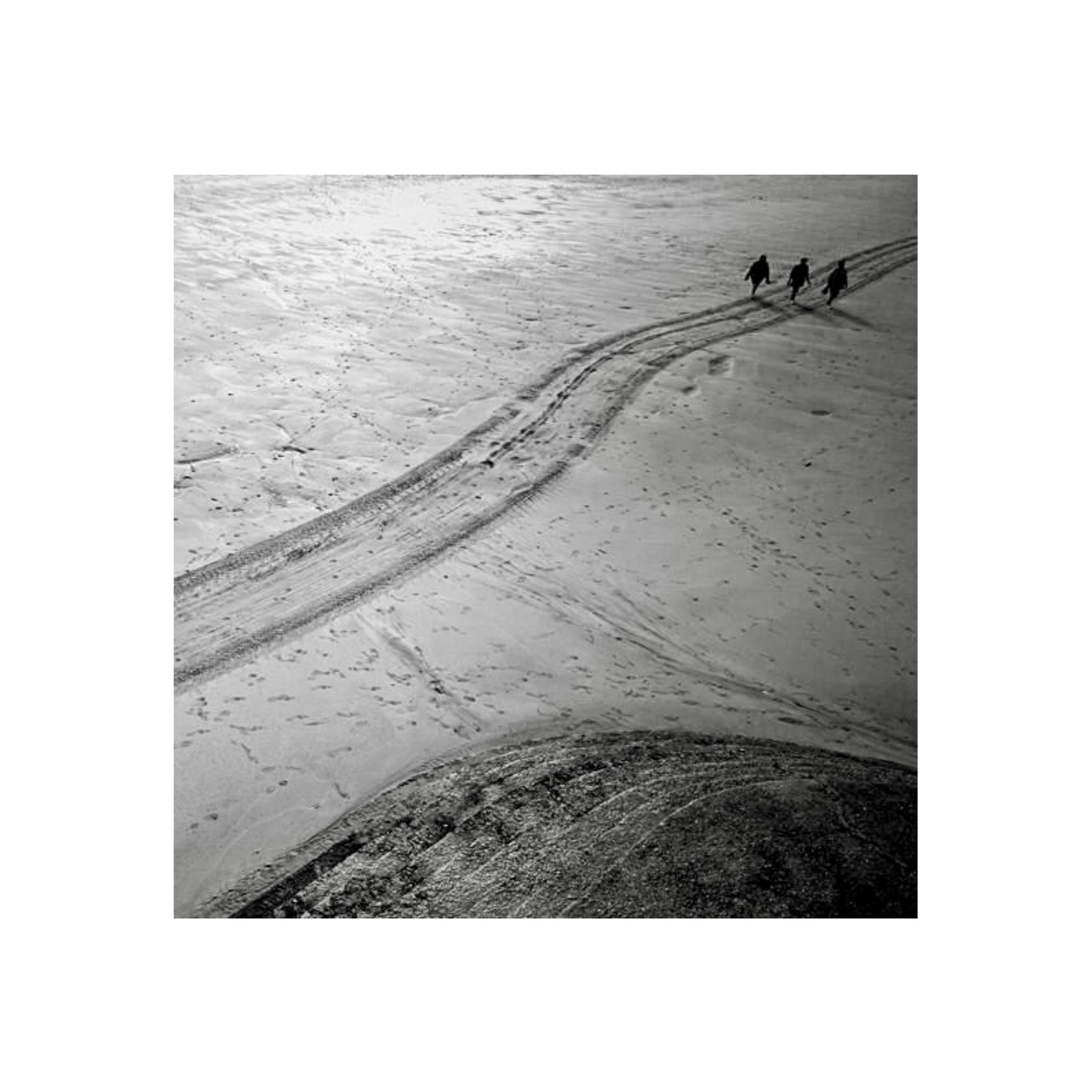

Amaro's photographic set is divided into three series: Trios, Triplos (Triples), and Trípticos (Triptychs). The number three appears in distinct forms: in Trios, it emerges as a visual element that becomes the thematic focus of the photos, captured serendipitously. In Triplos and Trípticos, however, the elements are arranged into collages that shape open-ended narratives characteristic of photomontages. In these series, the number three, while foundational to the work, is not always explicitly evident—especially in Triplos, where additional elements complicate the identification of the "third" subject in a scene. Amaro's intent is to "inspire narratives and subjective fabulations."

In the photomontages, images are "planted" and arranged, as is typical of this method, granting them movement and unpredictability. This characteristic of photomontage—where combinations generate chance outcomes—opens space for varied interpretations, offering viewers countless associative possibilities. Thus, the generative three evolves into "n" probabilities, a concept that resonates with philosopher Henri Bergson’s ideas about consciousness, time, and space, where the unpredictability of existence gives rise to fabulations.

The unpredictable, contrary to assumption, is not confined to the collage-like images but is also present in those where objects and people are encountered serendipitously, as well as in those with compositions unfolding like short stories, as seen in the Trípticos. In the Trios, serendipity emerges in the viewer’s perception after the photograph has been taken—three motorcycles, three boats, three chairs, three black shapes, three people with floats, three individuals walking on the sand. In contrast, in Triplos and Trípticos, the three is embedded in the creation process and the subsequent combinatorial analysis. For Bergson, this mutability defines the essence of existence, as consciousness in existence generates change.

Amaro’s images revolve around constructing diverse temporalities and spatialities, forming a multilayered collection of times within recognizable spaces. This transforms the experience of reality into an imagined one: the present in Trios, the surreal atmosphere of Triplos, and the narrative time of Trípticos. The unexpected arises as ruptures within the images, as reality is reimagined and invented.

The inventiveness of this photographic group points to the experimentalism characteristic of modern photographic production, which began to take shape in Brazil during the 1940s. Analog photography was still the predominant technique, and images were largely black and white. However, conceptions of representation were shifting, foreshadowing the advent of digital imaging systems and the interventions that would later define contemporary digital photography. This era marked the start of significant experimentation, with works that resonate with Amaro’s, such as German Lorca’s emblematic Circo de Cavalinhos (1949) and Janela – Só para Mulheres (1951).

When examining the aesthetic connections of Amaro's work, one must also consider the role of surrealist photomontages, which offered a counterpoint to the documentary desire to depict the factual—a prevailing approach for much of photography’s history. This experimental wave intersected with the evolving paths of visual arts, as photomontages introduced ruptures in reality, revealing—without fully exposing—the subjectivity of the creator and observer. This immersion into the imaginary is especially evident in Triplos, which could be compared to Athos Bulcão’s photomontages from the 1950s—a connection that deeply resonates with Amaro.

As is typical of photomontage, the scenes in Triplos present interpretive clues that, from afar, resist yielding logical conclusions, leaving viewers unsatisfied in their quest for definitive knowledge. What remains evident throughout these works is that the stories are told under the open sky: no space is enclosed. The imagined interior unfolds beneath a visible sky.

Amaro himself states: “I aim precisely at what I want, frame it, and press the button; there’s no secret.” He adjusts the grayscale tones subtly to achieve the desired effect. While there may be no mystery in his method, the resulting photographs are of high quality, with excellent framing and focus, bringing to life the mundane—boats, stones, or chairs—transforming everyday objects into subjects worthy of contemplation. This decisive capture, particularly evident in Trios, is reminiscent of American photographer William Eggleston’s approach to observing and capturing situations, objects, or scenes with intense prior scrutiny—a process that precludes the need to reshoot.

In Trípticos, another image-capturing and crafting process seems to occur. Conceptually positioned between Trios and Triplos, or between chance encounters and the combinatory constructions of images, the stories unfold in non-linear sequences. Theatrical and cinematic influences, languages familiar to Amaro’s professional life, contribute to the conception of this series. As the name suggests, Trípticos are formulated in thirds: three moments interwoven into small visual tales that, while sharing formats, differ in their narrative focus.

Amaro’s collection, enveloped in black and white, invites contemplative exploration. Despite its multitude of interrelated elements, the photographs maintain a meditative silence, drawing viewers into a reflective state as they seek meaning in the openness these images offer. To truly see, one must observe, engaging with past, present, and future to allow the magic of this photographic group to emerge.