ROSANA MOKDISSI

(text for folder)

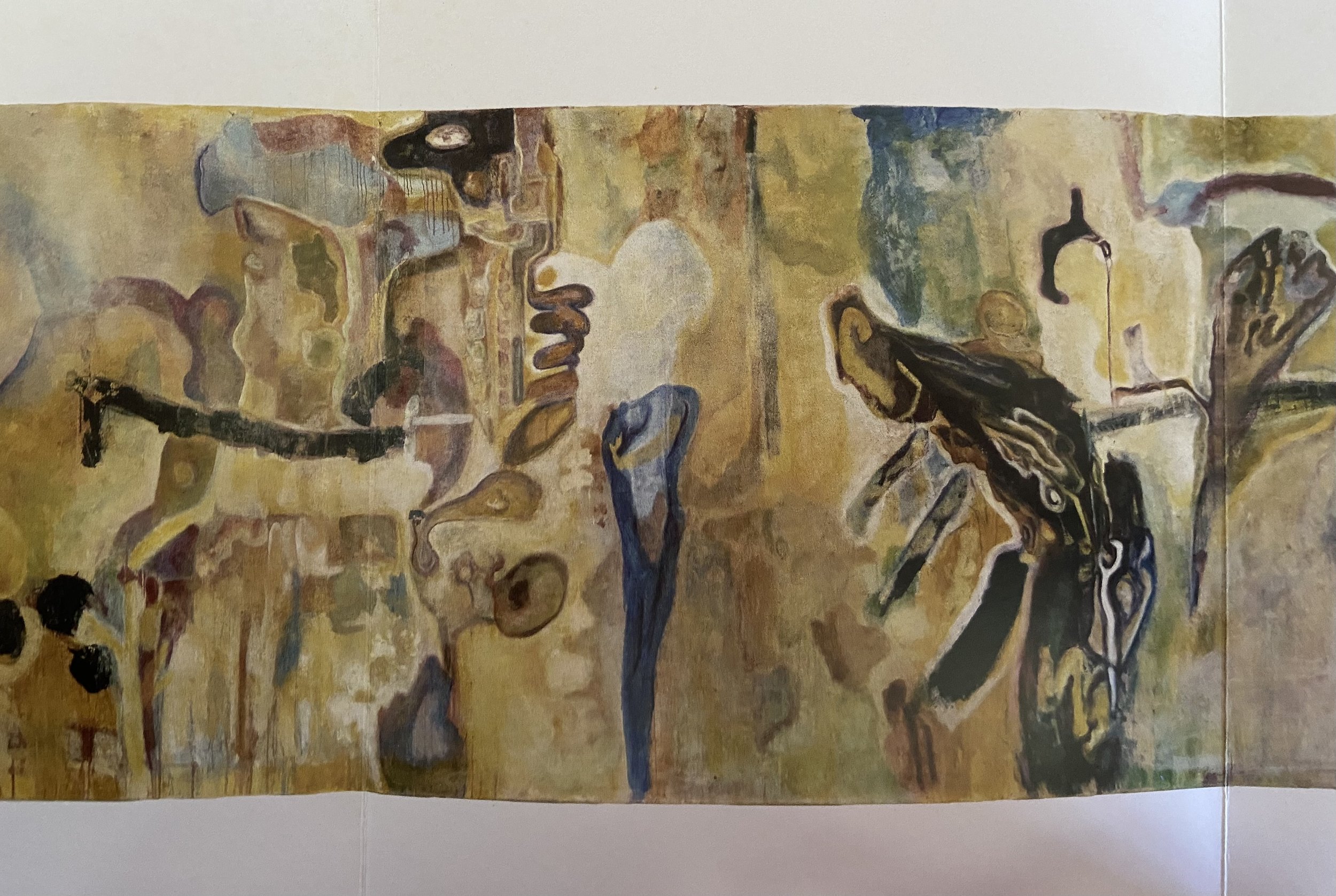

I. A Drifting Gaze.

The story to be told speaks of a journey through a certain painting. It is long and narrates fables and legends that reside in the imagination of those who view it. And it is from the place of those who have seen the painting that this text begins, a writing that flows without an exact direction and does not aspire to a conclusion, for the viewer is the contemporary subject imbued with language in which the type of discourse consists of fragments of memory, desires, and certain acquired knowledge. What is proposed to the reader and the observer is wandering—the act of walking aimlessly, without precision over the body of this large painting. The most natural path to take— which is a paradox!—would be one that links the fundamentals of painting to its much-lauded death. Regarding the divergences between painting and modernism, it would be an analysis of them in their infinite correlations with the history of color, form, light, and shadow. To speak of painting and its confrontation with the limits of its medium. Of the crisis of representation. To discuss abstraction in relation to the outside world and narrative—the inside.

II. A Certain Archaeology for the Gaze: On the Great Panel.

The pause of the gaze ends. The wanderer continues the journey across the surface of the canvas. Light has taken the place of shadow in the passage across the map, and what we see are varied shapes and differently shaded forms. What is defined by these forms are traces of someone or something—a man, an animal, a crustacean, perhaps?—that point us in a direction but do not quiet the unease in the search for the definitive. However, there is no narrative in this; what does this painting tell us? Like an archaeologist seeking the past to understand the present, we can view Rosana's painting as a palimpsest, a surface that has received multiple texts at different times. The surface that received each of these texts, erased to give light to another: it is a spectacle of memory. Again, we encounter time crossing the space in depth, widening the flat surface of the canvas.

III. Painting as a Map: On the Space Within.

Throughout this painting, we sometimes see shapes and colors with more precision, and at other times, we sense them. It is a different procedure from what we take when looking at narrative paintings, where there is a focal point from which the thread of the story begins—seeing equates to knowing—we can enter this painting from any direction and trace relationships between one image and another. Thus, we feel around, searching for a resemblance to something already seen, already known, in order to establish points of contact between images. We search for this link in memory, whether distant or near. But it is not only the observer who seeks these memories. The artist also looks for this connection in the meaning of their expression, also denied to them as it is, ultimately, an existential search. Charles Baudelaire, commenting in the 19th century on the painter who uses memory—“mnemonic art”—and dispenses with the model to express and capture their object, writes: "He (the artist) fears... not acting quickly enough, letting the ghost escape before its synthesis has been extracted and captured... so that the ideal execution becomes as unconscious, as fluid as digestion for the healthy brain of a man who has just eaten."

In this map that is the painting, not only is space traversed, but time as well. These two conditions are inseparable but not necessarily reconcilable. At the moment the journey begins, shadows take the light of day. It is the moment of twilight, where the word “almost” can be used. Where we are

not allowed to enter, only to conjecture, because painting, as one of the oldest forms of expression, finds in abstraction—a term complicated by its own definition—the will not to represent and takes the individualization of experience as one of the basic terms of its glossary. Perhaps because of its irreproducibility, painting becomes a focal point of resistance. The areas our gaze traverses and

finds meaning absent are moments of void, of true lack. Resistance springs from those areas of the painting where space is unoccupied. In the pause, everything is allowed because there is silence. It is Jean Baudrillard, the theorist of hyperreality, who tells us, questioning the effect of the often stagnant profusion of modern reality on the subject: “It is what we have unlearned in relation to modernity: it is subtraction that gives strength, from absence comes power. We insist on accumulating, adding, inflating. And we are no longer capable of facing the symbolic domain of absence.” What we have, after all, is the presence of this/these painting(s) and our reception of them.

IV. From Inside to Outside: The Painting in One of Its Possible Stories.

At some point in the journey, the viewer’s gaze moves away from the internal space of the painting and looks to the outside, to history and culture, and the question arises: how does this/these painting(s) fit into the history of art? In this territory to be explored by imagination, the images offer themselves to countless readings, including those that attempt to create links between the appearance and meaning of what is presented in the canvas and what belongs to history. In the case of painting, they raise issues that have accompanied it with a mark since its distant appearance, in a stream of analyses that cannot be fully presented here. For now, considering the construction of the pictorial universe in question, in which the large canvas presents itself as an Index, Rosana draws closer to a group of artists who sought to develop visual codes, an “abstract iconography,” as Giulio Carlo Argan wrote.

That said, the Italian historian referred to the paintings of the Armenian artist*, associated with a branch of Abstract Expressionism, who flirts with the figure and with whom Rosana shares points of affinity, especially in relation to the series of paintings created toward the end of the artist's life and career, when he had reached artistic maturity. In the paintings of both artists, there are similarities in how the forms are located in space—sometimes combining, sometimes distancing, alternating between blocks of indistinct masses and individualizations of form. Also present in both bodies of work is a sense of strangeness brought about by the presence of figures that we might call “biomorphic.” This type of figure, the result of a symbiosis between the animal and vegetal worlds, is characteristic of a production aligned with certain surrealist operations, and it is also found when encountering the works of the Chilean Robert Sebastian Matta, who creates atmospheric painting, distributing on his surface figures that allude to a natural and supernatural world to which access is limited.

Each figure demands its own specificity amidst the multiple colors and shapes. The subject who gazes still tries to see beyond the more defined outlines, entering a space suggested by a kind of mist of colors in the background, but loses, for a moment, the line of the map. We can say that this wandering through the painting is one of the possible methods of reading, even when it does not resemble a method of scientific rigor. It could not be otherwise, given that each of the interventions appearing on the canvas—the gesture, the color—or its evanescence, and the hybrid forms are signs pointing to possible meanings, which transform as new articulations are made. Thus, the drawing of the map becomes complex.

This inconclusive method, which leaves Rosana’s work open to multiple readings—the absence of titles for her works also points to this path—finds a kinship with the method described by Argentine fiction writer Alberto Manguel, when he writes about the abstract painting Dois Pianos by American artist Joan Mitchell, from 1980. Manguel observes the impossibility of “translating the untranslatable” in a painting that presents “possible layers of reading.” Thus, the possible method allows “a new reconstruction of our impressions through our own experience and distorted knowledge, while we tell ourselves narratives that transmit not the Narrative, never the Narrative,

but allusions, insinuations, and new assumptions.”* And in this simultaneous movement of discovery and emptiness, Rosana’s paintings find their place.

V. The Right to Drift: Returning to the Beginning.

When turning attention back to the large canvas, the subject pauses at the figure occupying the central position. Its dark color and the profusion of details contribute greatly to the eyes being placed upon it with greater care. But soon, one perceives a faint blue stain to the left—in a movement opposite to Western reading and favoring the attitude of the wanderer. This fragile figure seems on the verge of being swallowed by the immense dark figure. Before this happens, the eyes have already moved to a denser, more populated area on the right of the canvas, where the spaces seem contested.

' Jean Baudrillard. A Arte da Desaparição. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. UFRJ, 1997 .P.83; Charles Baudelaire. Sobre a Modernidade: o pintor da vida moderna. Org. Teixeira Coelho. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Paz e Terra, 1996. P 32.; Giulio Carlo Argan. Arte Modema. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1992. P. 615; Alberto Manguel. Lendo imagens: Uma história de amor e ódio. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2001. P. 54-5.

*Arshile Gorky.